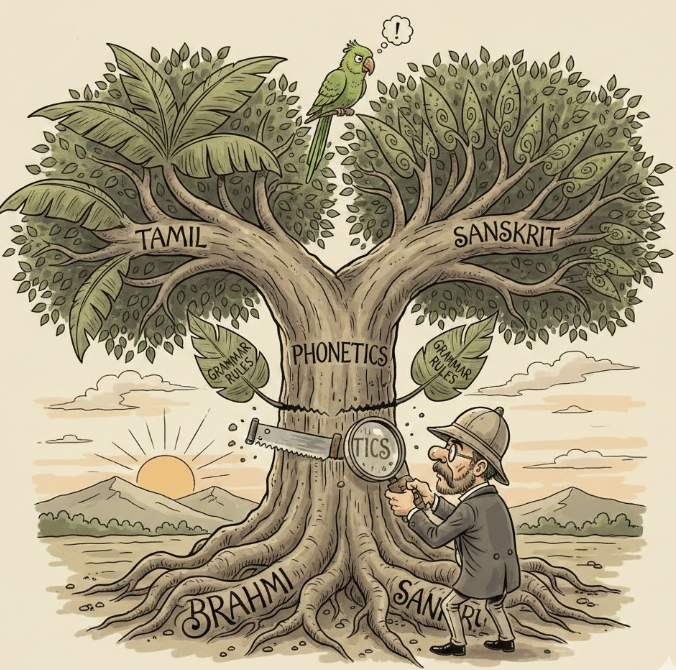

In our previous articles regarding this anti-Sanskrit hatred, and in some other parts of the Ravana Politics series, we have written about the similarities between Sanskrit and Tamil. Alright! We decided to write a comprehensive article explaining why we consider classifying Sanskrit and Tamil into two different language families a mistake, and why those who classified them did so.

You might have watched the Tamil movie Anniyan (directed by Shankar, starring Vikram). In it, the character Anniyan would recite a sloka while making an entrance, or he would punish wrongdoers while reciting a sloka.

A question always kept running in my mind: “How could you arbitrarily divide all Indian languages into two completely different language families, despite them having so many similarities and a connected foundational structure?” They reason that the grammatical structures of the two are different, and hence the division. I couldn’t accept that even then. The question of why they solely used grammatical structure as the yardstick when dividing languages into families kept haunting me.

This morning, Lalli Miss (the teacher who taught me basic Hindi and Sanskrit) had kept a Tevaram hymn on her WhatsApp status. Seeing that, the slokas in the Bhagavad Gita came to my mind. It was at her house that I first learned the Gita.

Why should a Tevaram hymn remind me of the Gita? It is exactly to explain this that we dragged the movie Anniyan into this article. The sloka Vikram recites in that movie is actually taken from the Gita. (Author’s note: Vikram also recites Garuda Purana slokas, but this Gita sloka aligns with the core theme of the movie).

“Sarva-dharman parityajya mamekam sharanam vraja Aham tva sarva-papebhyo mokshayishyami ma shucha”

“Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear!” – This is the meaning. But we don’t need that right now.

When I was learning some chapters of the Gita in Sanskrit, I noticed something. In the book I had, a sloka would be printed in two scripts: Devanagari and Tamil. They would leave a space between words in the text of the sloka. But when we actually pronounce the words, we cannot leave a space exactly as written.

For the sake of the rhythmic flow (meter/sound) of a sloka, words are split, joined, and shuffled. In “Mamekam,” there are actually two words: Mam and Ekam. But based on the sloka’s phonetics, it is written continuously as Mamekam.

“Karmanyevadhikaraste Ma phaleshu kadachana”

The above sloka means: “You have a right to perform your prescribed duty, but you are not entitled to the fruits of action.” In this, “Karmanyevadhikaraste” (You have a right only to perform your duty) consists of four words that have fused into a single word for the sake of phonetic flow.

Karmani (In duty) + Eva (only) + Adhikarah (right) + Te (to you).

You cannot find this in European language songs. But you can find it in Tamil poetry (Seyyul). Every Tamil poem has a specific sound meter. Poems have phonetic measurements.

Aadal purindha nilaiyum Araiyil asaitha aravum Paadal payindra palbhootham Pallaa yirangkol karuvi Naadar kariyathor koothum Nankuyar veerattanj soozhnthu Odung kedilap punalum Udaiyaa roruvar thamarnaam

This is the Tevaram song Lalli Miss shared this morning. In this, the word Pallaayiram (Pal + Aayiram) is split and written as “Pallaa yiram”. The words Nanku + Uyar are joined and written as “Nankuyar”. Just as the poetic structure and its rhythmic sound were given importance in Tamil, it was exactly the same in Sanskrit.

Alright! How is this practice of tearing apart, shuffling, and fusing words possible for both Sanskrit and Tamil? Why isn’t it possible for European languages?

The reason is the alphabetical structure and its inherent similarities based on script and phonetics. That is what enables both Sanskrit and Tamil to write words according to the rhythm and phonetic measure of the poem.

It is only because both languages have the “Abugida” (Uyir-Mei / Vowel-Consonant) structure that the final consonant of one word and the first vowel of the next word merge to transform into a completely new ‘Uyir-Mei’ (syllabic) letter. These ‘Uyir-Mei’ letters facilitate the creation of rules for joining two words together. In Tamil, these are called Punarchi rules, and in Sanskrit, they are called Sandhi.

European languages like English do not have this ‘Uyir-Mei’ writing system, nor is their alphabet like Tamil and Sanskrit. In both Tamil and Sanskrit, ‘A’ sounds strictly like ‘Ah’ in all words. Additionally, Sanskrit has four phonetic variants for letters like ‘Ka’, ‘Cha’, etc.

In European languages, ‘A’ doesn’t sound like ‘Ay’ everywhere. You cannot compare the similarities shared by all Indian languages—based on script and phonetics—with European languages.

We can see this similarity in almost all traditional Indian languages.

In both Sanskrit and Tamil, it is strictly defined where and for how many ‘Mathras’ (measures of time) a letter should sound. They possess a mathematical calculation for this: Short vowel (1 Mathra), Long vowel (2 Mathras), Consonant (1/2 Mathra). This science of measuring and writing sound with such precision exists nowhere else in the world except the ancient Indian subcontinent.

No letters are unnecessarily present in a word. When ‘no’ sounds like ‘noh’, why do we need a word like ‘Know’? This is a massive flaw in European languages. You cannot find such things in Indian languages, which are built on phonetics-based scripts and structures.

In English, we write “An Apple”. When speaking or singing, we pronounce it together as “A napple”. But when writing, we cannot write it as “Anapple”; if written so, it is a grammatical error (Spelling mistake). The reason is that their system is an “Alphabet” (individual, separated letters).

However, all languages in the Indian subcontinent possess this philosophical “Abugida” (Uyir-Mei) structure—akin to a body (Consonant) and soul (Vowel) merging. The brilliant grammatical mechanism where words in a line merge with the vowel of the next word, transforming and bending for the sake of rhythmic flow—called Punarchi or Sandhi—is common to both Tamil and Sanskrit.

These Western researchers divided languages into families. First of all, the necessity for this is unknown. What did the people who divided them do?

Both Sanskrit and Tamil share the exact same script base: Brahmi. If asked whether they belong to the same family, they declare “Invalid! Invalid!” (referencing the iconic dialogue by the village headman in the Tamil movie ‘Nattamai’). Okay! Since both have the structure of Vowels, Consonants, and Vowel-Consonants (Uyir-Mei), can we place them in one language family? Again, they declare “Invalid! Invalid!”. Wow! If you separate the ‘Aryan’ language of Sanskrit from Malayalam, Telugu, and Kannada—which you have classified as a ‘Dravidian’ family—those languages simply cannot function. Yet, they say it’s completely invalid.

They claim, “We divide language families based on grammatical rules, like how verbs change.” This makes one ask, like the comedian Goundamani asks Senthil (in the classic Tamil comedy movie ‘Karagattakaran’): “Who the hell told you that it must be divided exactly like this?”

Here, they say that in Sanskrit, a verb changes its base root completely when referring to different tenses. When asked, “Doesn’t the same happen in Tamil?”, they reply, “It changes, but the manner in which it changes is different.”

Sanskrit example: Root word: Vid (To know) Present tense: Vetti (He knows) Past tense: Veda (He knew) (Here ‘Vi’ internally transforms into ‘Ve’).

Root word: Gam (To go) Present tense: Gacchati (He goes) Past tense: Jagama (He went).

In Tamil, the root word Vaa (Come) transforms into Varu-Giru-Aan = Varugiraan (He comes) and Van-th-Aan = Vandhaan (He came). They say it doesn’t break and transform internally like Sanskrit. Tamil stacks parts of the verb like laying bricks (Agglutinative). Sei-Seithen-Seigiren. Sanskrit fuses them like melting two metals into an alloy (Fusional).

Even though there is a difference in how verbs transform, fundamentally, this change can be classified and explained using Punarchi and Sandhi grammar in both languages.

Sanskrit explains how “Gam” became “Jagama” through a sutra (formula) in Panini’s grammar. You cannot use Punarchi and Sandhi rules to explain the European English words “come – came, went”.

Western researchers said Sanskrit breaks and changes verbs internally (Fusional), hence it belongs to us. But looking at them, we must say that even if Sanskrit breaks and changes like that, it transforms subject to a precise grammatical rule (Rule-based), just like other Indian languages. There are many loopholes in the foundation they kept to divide languages based on verb conjugation.

In both Sanskrit and Tamil, the action and the doer can be encapsulated in a single word. Is that possible in European languages? You are forced to write “He went.”

Therefore, it is only from the foundation of script and phonetics that verbs transform. Sanskrit and Tamil differ only in how they transform, but fundamentally, they share many similarities.

Both shared the same script system, Brahmi. Both have various common or shared words. In a Tamil word discovered in the Brahmi script in the Egyptian pyramids, ‘Sigai’ (hair) is recognized as a Sanskrit word. This could point to a stage that predates both Tamil and Sanskrit.

In Chinese, English, and French, there are no pronunciations like Ta, Na, La, Lla, Ra, Na (Retroflex sounds – rolling the tongue backwards to pronounce). But these pronunciations exist in all languages of the Indian subcontinent: Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and Sanskrit. Retroflex sounds (‘Ta’, ‘Na’) exist in Vedic Sanskrit itself. These sounds are absent in Indo-European languages like Latin and Greek.

As for the European researchers, they did not take into account words, letters, or phonetic systems. Those who classified language families based on the grammatical structure of verbs did not consider that Tamil also has a system of auxiliary verbs similar to European languages. They didn’t consider that Japanese and Korean have a system of attaching suffixes to root words, exactly like Tamil verbs. Can you place the Japanese language in the Dravidian language family for this reason? You cannot.

How should a language family be classified in the first place? Just as biological taxonomy has a hierarchy (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species), linguistics should also have a hierarchy, and in that, Sound & Letters must be at the top.

Why should sound be first in language classification? We classify living beings according to their habitats and lifestyle. A dog and a tiger do not make the same sound. The phonetic systems that evolve in one geographical area are not identical in another area; this is exactly what shows the difference in phonetic systems among languages.

Just as a tiger, lion, and leopard naturally share the trait of making a similar kind of roar, Indian languages naturally share many similarities in their phonetic systems. After the phonetic system comes the script. This is also a mark of civilization. From that perspective, for all Indian languages—whether Sanskrit or Tamil—the Brahmi script served as the root. Letters pronounced by rolling the tongue back exist only in Indian languages. If we take grammar after all this, conceptually, many grammatical structures are identical in Tamil and Sanskrit. Like the Punarchi rule in Tamil and Sandhi in Sanskrit, these grammars are fundamentally based on the phonetic system. Dividing two languages into two different families solely based on the variation in how verbs transform is absurdity, not an intellectual study.

Suppose my great-grandfather had a great-grandfather. During my grandfather’s time, the extended family separates, migrates, and undergoes evolutionary growth. I am the continuation of that growth. Suppose my child possesses more of my wife’s traits and only a few of my traits. Does that mean my child does not belong to my great-grandfather’s lineage? Suppose my child’s character is like my wife’s, but the face looks like mine. According to the logic of Western researchers, I belong to one family and my child belongs to another. They have classified language families by completely ignoring how a language can undergo evolutionary growth (evolve).

A person understands anything based only on the environment in which they grew up. If someone who has never seen a cow—someone who grew up in their town seeing only pigs or deer—comes to our town and studies a cow, how would their intellect work? It would naturally think, “This is a four-legged animal similar to a deer or a pig from our town,” right? That is exactly what the Western researchers’ studies about us are like.

He doesn’t know the culture. He doesn’t know the nuances of language phonetic systems. He wouldn’t know how these two languages must have influenced all the languages across India. However, they very conveniently grouped Sanskrit with themselves, split Indian languages in two, thoroughly confused us, and left.

We must study about ourselves. Without Western influence. We must research without the bias of “I am a Tamilian, you are a Panipuri-seller (North Indian).” If Telugu and Tamil came from Sanskrit, we must accept it. If there are Sanskrit words in Thirukkural, we must accept it.

We must reject as lies the studies that used rules convenient to them to dissect a unified culture and classify it into Aryan and Dravidian.

Let us know ourselves! Using our own intellect! (We learn about us not using Western knowledge, but using our own knowledge).